Rainer Ganahl, at Galerie Roger Pailhas,

November - December 96

by

Thomas F. McDonough

PARIS

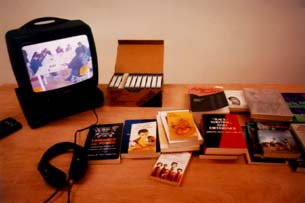

"Installation view" Roger Pailhas, 1996

-

To my knowledge, no one has yet written a history of the coffee-table

book. This is a shame, for these glossy, oversized volumes, which place

a premium on reproduction quality while relegating the text to the status of

glorified caption, are paradigmatic of a particular moment in the history

of taste. While I wonít attempt to compose this history in any detail, I

would like to essay a few pertinent remarks or observations. First, I

suspect that the coffee-table book underwent a fundamental transformation

in the early 1980s. As a publishing genre, it arose in the 1950s with cheap

methods of image reproduction and a growing audience of petit-bourgeois

suburbanities eager to appropriate the culture of their social better;

characteristic of this moment in its development are the ads one can find

in the back of any number of Art News issues from this decade, "The

History of World Art' in 15 Volumes, only $9.95 each, shipping and handling

included!" This mass democracy model perished with the economic retrenchments

of the 1970s,

and the coffee-table book was reborn in what might be called

its mock-aristocratic mode with the dawn of the overblown art market of the

following decade.

In this incarnation (shall I call it a process of "Rivvolification?"), the book retained its basic format but targeted a very different audience. No longer the accessory of the oak-veeer table in a Nassau County living room, it would now grace the antique piece artfully set within a Soho loft. The nouveau-riche entrepreneurs of the 1980s, eager to prove their cultural savvy, exemplified the new consumers of the art book. Two facts bear this out: the new prices of these books,which regularly surpassed $100, putting them well outside the range of the mass of readers; and their new subject matter. If the first generation of coffee-table books had intended to introduce a broad public to the "legacy of Western civilization," this revamped version was decidedly contemporary and exclusive. Suddenly, the Old Masters were out, replaced by the latest superstar to grace Mary Booneís walls. An abundance of high-quality color reproductions of carefully selected works from the right private collections and a text, now, often written by an important pseudo-academic or art critic-publicist, are worked together to make a powerful engine for the social legitimation of a new generation of professional cadres.

"Imported-A Reading Seminar (French Version)" 1996

Perhaps the greatest constant in its history is the fact that the coffee-table book is one of the first appearances of this curious phenomenon known to an impoverished society: the book that is not intended to be read. It is only meant for display, one need merely own it for its work to be accomplished. The art book is, one could say, the very image of cultural passivity. These thoughts were prompted by Rainer Ganahlís most recent solo exhibition at Galerie Roger Pailhas in Paris. For me, the centerpiece of this show was, to paraphrase the title of one of Ganahlís works, a "reinvented coffee table" this site of passivity and social legitimation turned against itself.

On top of a simple wooden table surrounded by chairs, rest 25 paperback books in English, French and German. They represent a sampling of literature in the field that, for lack of a better name, has come to be known as "Cultural Studies." Careful examination reveals a more willful selection: themes of critical ethnography, anti- and post-colonial polemic and Franco-Algerian fiction predominate. Inside each book, the title page is ink-stamped: "A Portable (Not So Ideal) Imported Library, or How to Reinvent the Coffee Table: 25 Books for Instant Use (French Version)." An artistís statement informs us that this piece, dating from 1994, is merely one installment of a series of "portable libraries" realized across the world in the past three years. Each version, selected with its country of destination in mind, is the basis of a reading seminar conducted by Ganahl, genereally in art schools, over the course of several weeks.

Next to these books on the table are a monitor and a box of video cassettes. We are invited to watch and listen any part of the complete proceedings of the seminar, held at the Villa Arson in Nice earlier in 1996, using the version of the portable library in question. The final element on the table is a draft of a book composed of interviews with various pillars of the academic left carried out by the artist. The ensemble composes a virutal "anti-coffee table book," for the passive spectator has no possible means to engage with this determinedly non-visual work and the aesthetic delectation glorified in these publications is effectively anulled. Ganahl removes us from the realm of exchange value and rudely thrusts us back into the world of use value. The only worth these inexpensive paperbacks have is in our ability to transform them into knowledge. (Although "inexpensive" here is only valid in comparison to the cost of a glossy art book,and the viewer sould not remain ignorant of the mechanics of the university-press market, which presents us with a seemingly endless stream of "critical theory texts" a subject that the artist seems unwilling to address.) The reinvented coffee-table book ideally acts as a tool of social delegitimzation aiding its reader to articulate and combat their oppression, the true aim of pedagogy.

"Imported-A Reading Seminar (French Version)", 1996

However Ganahlís practice is not without itís weaknesses and evidently, its contradictions. A series of color photos taken during the course of several reading seminars, which show the artist and students tackling the various texts of the "portable libraries," occupied the main room of the gallery. It is difficult to be certain of what we are seeing here: for example, Ganahl is eager to point out one photo of a young man reading Fanon, telling us that his "family is from Algeria" are we to assume then that the photo depicts a moment of enlightenment? His look of concentration could mean any number of things. These photos may have some interest for what they reveal of the pedagogical process, its alternating moods of boredom and excitement, but as such, they differ greatly from the more radical implications of the portable library. For we remain passive before the photographs, spectators at someone elseís learning, whereas sitting at the table, we must take an active position if we are to have any access to the work. Ganahl may have reinvented the coffee table, but its memory lives on.

Thomas F. McDonough

Email: ThingReviews

To post a response fill out the following form and click the "Submit" button. Or go back...

Scroll down to read messages.